Chris Reed: Abuses of prosecutorial discretion go far, far beyond Jeffrey Epstein

When a DA can “indict a ham sandwich,” overprosecution may be a bigger problem than underprosecution

In the idealistic view of the role of the prosecutor in the American judicial system — of someone like Jack McCoy in “Law & Order” — it’s the burning desire to do the right thing that guides prosecutorial decisions. In episode after episode, McCoy (played indelibly by Sam Waterston) pushes back against everyone, against reluctant witnesses, detectives who cut corners, bosses playing favorites and anyone who gets in the way of bad guys getting their due. As the Bitter Script Reader blog noted about McCoy in 2010 when the series went off the air ...

He’s the prosecutor we all wish was representing us, the guy who looks beyond politics and goes strictly after justice.

His isn’t the real system, of course. As the current headline-making Jeffrey Epstein case illustrates, plenty of prosecutors’ decisions would make McCoy want to vomit.

The Miami Herald brought the scandalous treatment of Epstein, a billionaire pervert, back into the spotlight in November. The newspaper offered a fresh level of detail on how federal prosecutors in Miami went easy on him despite the fact that they knew that ...

Beginning as far back as 2001, Epstein lured a steady stream of underage girls to his Palm Beach mansion to engage in nude massages, masturbation, oral sex and intercourse, court and police records show. The girls — mostly from disadvantaged, troubled families — were recruited from middle and high schools around Palm Beach County. Epstein would pay the girls for massages and offer them further money to bring him new girls every time he was at his home in Palm Beach, according to police reports.

In spite of vast evidence that could have yielded Epstein a life sentence, Miami U.S. Attorney Alexander Acosta — now, incredibly, U.S. labor secretary — shelved and sealed a federal indictment of him. State prosecutors sentenced him to only 18 months in custody, which he served in the private wing of the Palm Beach County stockade on a work-release program.

Epstein — arrested Saturday — is finally getting the prosecution his conduct deserved from federal prosecutors in New York.

The Boston Globe columnist Michael A. Cohen deftly described the outrage felt by so many over this case:

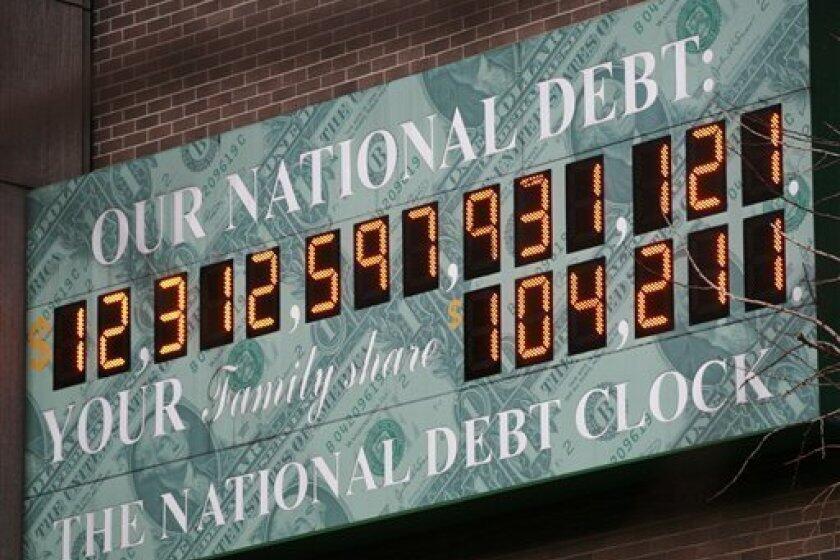

That Epstein’s victims have had to wait so many years for justice to be done — and that Epstein could continue to engage in predatory behavior — is yet one more disturbing reminder that we have two justice systems in America. One for the rich and well-connected, who can game the system, throw money at their problems, walk away unscathed, and never have to say they’re sorry, and one for the rest of us.

But questions about prosecutorial discretion should extend far beyond decisions to go easy on wealthy, well-connected defendants. The problem on the other end of the spectrum — of going after some defendants with little or flawed evidence — is also acute. The joke that a district attorney can “indict a ham sandwich” isn’t really a joke. It’s the truth in America’s deeply flawed judicial system. As Bennett Gershman wrote in The Daily Beast in 2015 ...

American prosecutors are powerful officials. They have the power to deprive people of their liberty, destroy their reputations, and even take away their lives. They have virtually unlimited discretion in how they exercise their powers.

And yet, they are essentially exempt from any outside supervision, oversight or accountability. As a result, they can abuse their powers with impunity. And prosecutors do just that, with devastating consequences both for individual defendants (especially people of color) and for the system as a whole.

The American Civil Liberties Union agrees, contending that prosecutors’ “harsh and discriminatory practices have fueled a vast expansion of incarceration as the answer to societal ills over the last several decades.” “When They See Us,” this spring’s Netflix miniseries about the “Central Park Five” — the New York City men wrongly convicted of a 1989 rape — offers an example of what Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz sees as the criminal-justice industry, in which the end product is convictions, right or wrong, and the goal is not justice.

A 2010 study by the Northern California Innocence Project backs this up. It found that from 1997 to 2009, there were 707 instances in California where a judge concluded that prosecutors had engaged in misconduct. Yet the state bar only publicly sanctioned prosecutors in six of those hundreds of cases. As The Appeal website noted ....

... even that number significantly underrepresents the problem: Most instances of prosecutorial misconduct do not result in a judicial finding in the first place, because the misconduct either goes undiscovered or is not taken seriously by the courts.

But government lawyers don’t just pick on minorities. After four people were killed in a wreck in a San Diego suburb in 2009 because a Lexus floor mat made the accelerator stick, Toyota faced a massive wave of lawsuits and negative media coverage over claims of unintended acceleration. While the dangers of wrongly installed floor mats were quickly documented, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration concluded in 2011 after a lengthy investigation that claims of other problems with Toyota were baseless.

“The verdict is in. There is no electronic-based cause for unintended high-speed acceleration in Toyotas,” said U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood.

As Forbes magazine reported in a piece headlined “Why Do Toyotas Hate The Elderly?” unintended acceleration claims were almost always made by older drivers with declining physical skills.

Yet in 2014, the Justice Department of the same Obama administration that had exonerated Toyota fined the company a record $1.2 billion in large part because of the volume of bogus claims. Why? A National Review analysis suggested persuasively that it was all about the optics, not the facts. University of Pennsylvania law professor David Skeel told the magazine ...

The timing of the original (2010) investigation seemed a bit suspicious, because it was in the midst of the American car companies’ woes. ... As for the new fine, one possible explanation is a desire to appear tough on global corporations in the wake of [Attorney General Eric Holder’s] much-criticized suggestion that some of the big banks are”too big to jail.”

So is there any way to separate politics from justice? To make sure everyone from the U.S. attorney general to the least experienced D.A. in Podunk County follows a Joe Friday-esque “just the facts” approach? Nope. Human nature being what it is, thumbs will be placed on the scale.

That doesn’t mean there’s not a way to reduce this problem. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch has a valuable thought. Last month, in a ruling in which he joined the court’s liberal faction in a 5-4 vote to invalidate a poorly crafted federal law relating to the use of guns in some violent crimes, he wrote ...

In our constitutional order, a vague law is no law at all. Only the people’s elected representatives in Congress have the power to write new federal criminal laws. And when Congress exercises that power, it has to write statutes that give ordinary people fair warning about what the law demands of them.

That’s what due process is supposed to guarantee — not the “justice is in the eye of the beholder” standard too often seen in the United States. But until Americans worry about prosecutorial misconduct on an ongoing basis — and not just when a sensational case like Jeffrey Epstein’s comes along — far too many people won’t have “fair warning about what the law demands of them.”

Reed, who has vacationed in Podunk County, is deputy editor of the editorial and opinion section. Email: chris.reed@sduniontribune.com. Twitter: @chrisreed99. Column archive: sdut.us/chrisreed.

Get Weekend Opinion on Sundays and Reader Opinion on Mondays

Editorials, commentary and more delivered Sunday morning, and Reader Reaction on Mondays.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.